The Matrix Organization | What Is It and How Does It Work?

The Matrix Organization | What Is It and How Does It Work?

By Susan Zelmanski Finerty

Author of Master the Matrix: 7 Essentials for Getting Things Done in Complex Organizations (2nd edition, 2022) and Cross Functional Influence: Getting Things Done Across the Organization

What is matrix organization in simple terms?

What is matrix organization in simple terms?

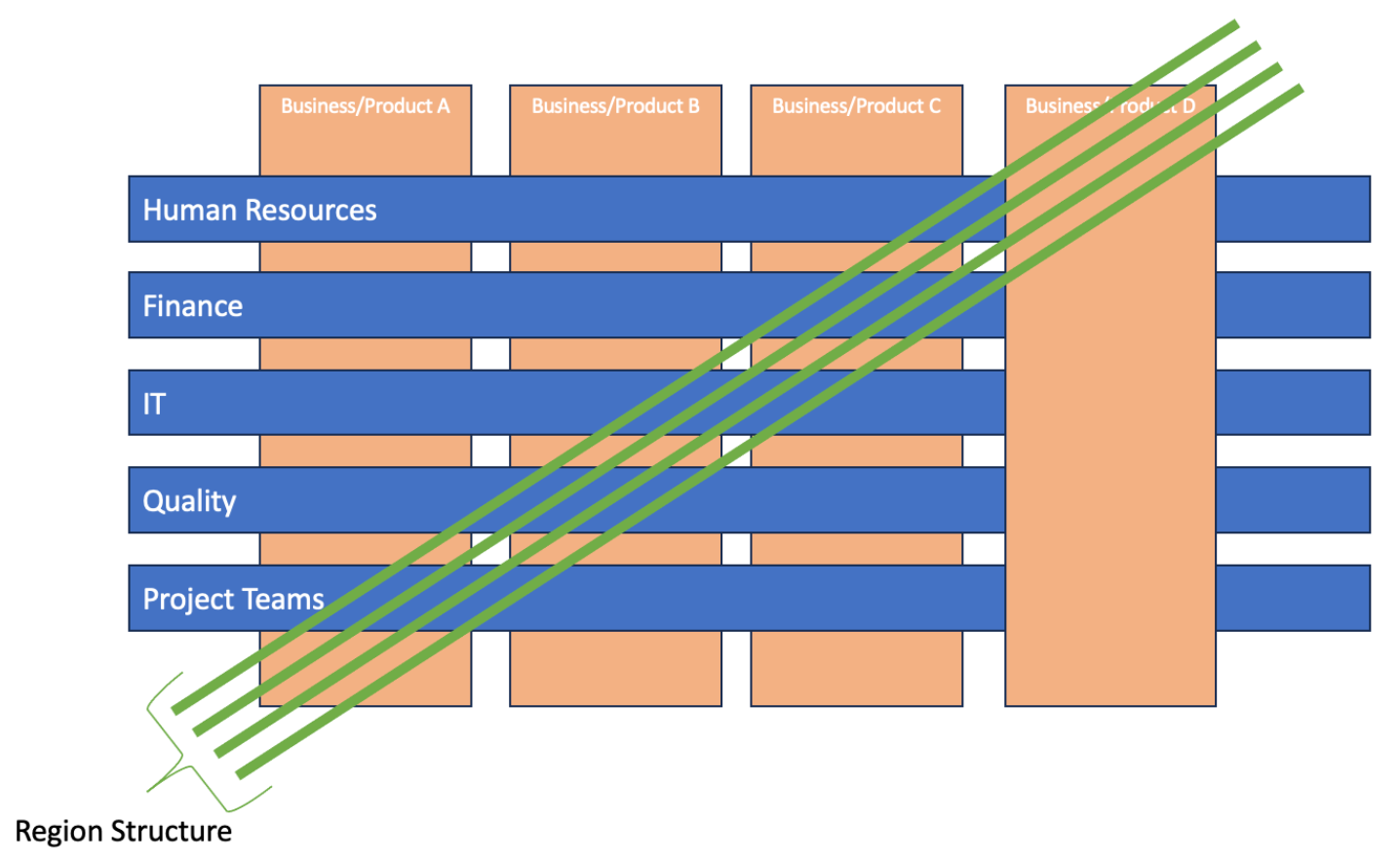

A matrix organization, in simple terms, means you have rows and columns in your organization. Matrix organizations are not only organized around business/product columns, they also have rows that cut across all columns. The rows come in the form of shared services (also called centralized functions, global functions, centers of excellence, etc), regional structures, and cross-functional project teams that operate across all parts of the business. For some, that means they will have multiple bosses. For all, it means thinking, acting and deciding beyond the boundaries of your immediate area of responsibility.

Is your organization like a lane on an expressway: fast, no lights or signs to slow you down? Or an intersection: congested, horns honking, various hand gestures flying? Or a traffic circle: information and tasks flowing in and out smoothly?

The reality is that most organizations start in lanes. If you’ve ever worked in a startup, you know the feeling—fast, full focus, everyone going in the same direction. In these single lanes, there is everything needed to support the business—from resources to develop products and services to sales, marketing and support functions. For a while, companies may be able to create a new lane each time they expand. Develop a new product—build a new lane. Expand into a new geography—build another lane.

But sooner or later, businesses realize that replicating lanes is a really expensive way to grow. And the more complex the product, the more expensive these lanes are. In addition, when your organization is built in lanes, people think in lanes. They don’t look to the left or right to see how their decision will impact others; they do what is right for their lane.

Finally, when you have lanes as your operating structure, you lose agility because your end users, clients, customers, patients, buyers, etc. have a lot of needs that don’t fall neatly in your lanes. When operating in narrow lanes, you can lose the ability to anticipate and adjust to their requirements.

So, organizations realize the financial burden of lanes, the way they limit enterprise-wide thinking and agility, and they create intersections, such as cross-functional teams and project teams that bring together all parts of the business, centralized shared services that support all parts of the business, and dotted and solid line reporting relationships that bring together two lanes through a single person’s reporting relationship. They create these intersections through organizational structure, and the matrix is born.

Unfortunately, a lot of organizations stop there—with a new org chart. If your only effort to work cross-functionally is a matrix organizational structure on an org chart, then chances are all you have created is a traffic jam (see previous comment about horns honking and various hand gestures). These intersections slow everything down, you get people crying for a return to lanes at best, and at worst, you’ve got people ignoring the intersections and sailing happily down their own self-made fast lane.

In order to reap the benefits (financial, enterprise-wide thinking and agility), you have to do more than create a structure, you have to change behavior. You need behavior that supports becoming more of a traffic circle than an intersection.

Interestingly enough, if we stick with the traffic circle analogy, we start to identify the behaviors we need to make a matrix work. What is key to navigating a traffic circle as a driver?

- You don’t stop, you have to yield

- Everybody has to go in the same direction

- There are fewer rules and it’s more ambiguous, so you have use judgment

- You have to be more aware of your surroundings

- You have a different connection with other drivers

Those five items just happen to be the foundation of working cross-functionally in a matrix organization. In order to effectively navigate a matrix, all parties have to be willing to yield (i.e. make trade-offs, defer to others’ decision-making and priorities), and everyone has to agree on direction (i.e. goals have to be aligned). Matrix organizations are inherently more ambiguous than traditional organizations. Where there is ambiguity, you rely on judgment, broad awareness, and connection with others. Navigating these realities are at the heart of the work we do with our clients.

If the work we do could be summarized in one word, it would be “flow.” Traffic circles seek flow. Matrix organizations seek flow. Our research, books, assessments, workshops and coaching focus specifically on what it takes to do this well—to create flow and ease congestion.

What is matrix organization with example?

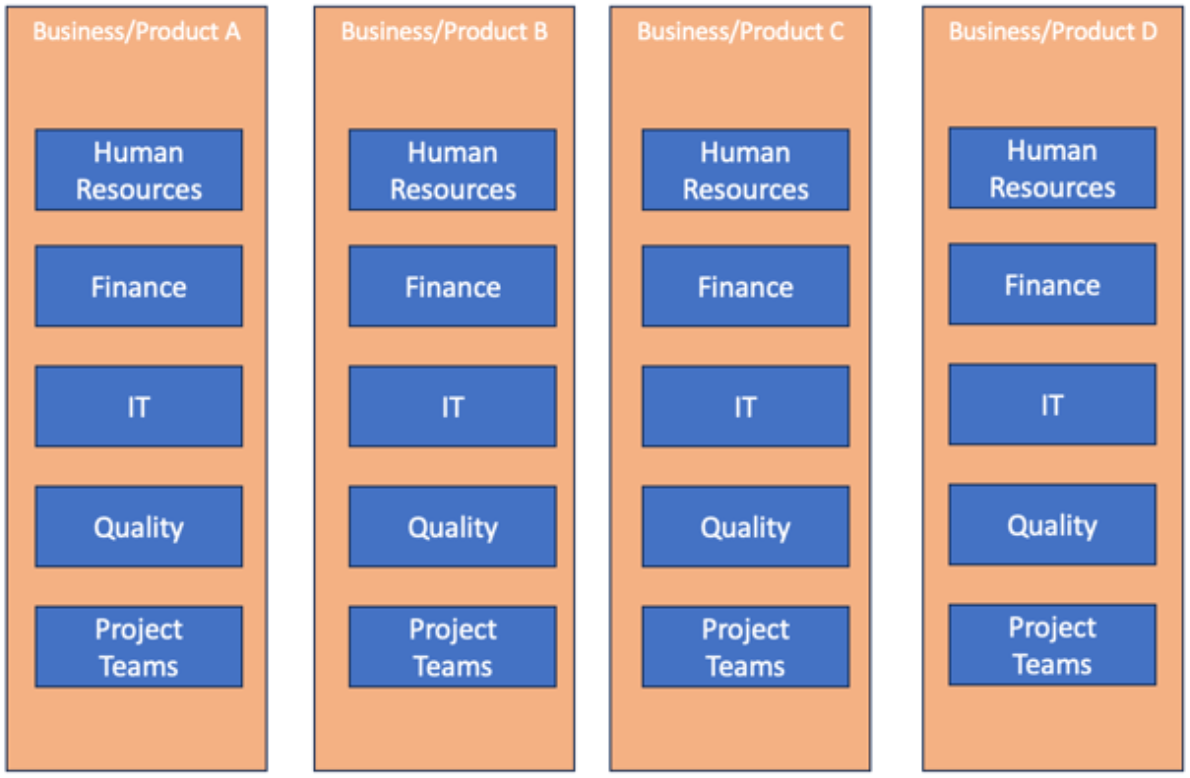

In a matrix organization, resources are organized in both rows and columns. A more traditional organization works just in columns (usually a business unit or product line) with dedicated resources in each column. Each column contains all the infrastructure and resources needed to “run” that particular business or product.

A non-matrix organization looks like this:

Matrix organizations are not only organized around business/product columns, they also have rows (usually functions, regions, or projects) that cut across all columns. The rows come in the form of shared services, regional structures, and cross-functional project teams that work across all parts of the business. In this way, specialized resources are shared across the organization.

Here is an example of a matrix organization:

Often (but not always) employees may have more than one boss in a matrix organization. For example, a person might be in the Finance function, supporting Business/Product B and report to a manager in Business/Product B (usually called a direct or solid line reporting relationship) and also have a manager in Finance (usually called an indirect or dotted-line reporting relationship).

This 2 minute video explains the what and why of matrix organizational structure in the basic terms, using the simple business model of a lemonade stand.

Types of Matrix Organizational Structures and Roles

Matrix Organizational Structures

Matrix structures take on many forms, outlined below. However, in reality, most organizations are a hybrid of non-matrix, matrix and even different forms of matrix structure.

Shared Services

The most common matrix structure is the shared service structure illustrated below. Organizations often centralize their functions—instead of having HR, IT, and Finance resources in every business unit, they create centralized functions (sometimes called a corporate function, a Center of Excellence). This not only leverages talent, it ensures consistency in policy, process and strategy.

Teams

Some organizations create a matrix in the form of cross-functional teams. These teams—you may know them as platform teams, category teams, market teams, core teams or brand teams—bring together all functions to plan, strategize and make decisions with the full organization and product life cycle in mind. The parts of the organization not contained in the teams organize their work around these teams (indicated by the green and orange waves below):

Regional Structure

As organizations grow globally, they find a need to create regional structures that can anticipate and meet local needs, while remaining linked to the broader organization strategy and achieving consistency in quality and branding.

Of course, some organizations employ all of these to create a multi-dimensional matrix, that looks something like this:

This is where the word ‘complex’ dominates the conversation. In these organizations, having a common understanding of what the matrix looks like, why it is in place and how people are expected to behave becomes essential to avoid the slow downs and traffic jams that occur.

Matrix Organizational Roles

In addition to looking at different matrix structures, people experience different types of matrix roles. We define four matrix organizational roles. These roles may differ in how and why they are set up, but they have common challenges and require common underlying skills and practices.

Formal Project Matrix

A formal project matrix is the most “traditional” and established form of matrix. It is defined as having a project management office structure and a functional or business reporting structure. These roles are very common for long-term projects, like product development. People are generally 100% allocated to these projects/positions. The idea behind this is to establish dedicated resources that utilize structured project management, but are still held accountable to the function or business that owns the final product.

Example: “I am an engineer on a product development project. On the ‘official’ org chart, I report to the Engineering Department Head. In reality I spend 80% of my time and get 80% of my work and direction from the project manager for a development team I am a part of—she’s my ‘dotted line’ boss.”

Cross-Functional Team Matrix

Cross-functional team matrixes have cropped up all over organizations as a way to solve problems and keep the business moving. They are generally for specific projects/issues. The idea behind this type of matrix is that more minds equals better problem identification and better solutions.

Example: “I am a member of an agile team building software that tracks clients from lead to deliverable impact measures.”

Reporting Relationship Matrix

A reporting relationship matrix is most often seen as an outgrowth of globalization. Often, globalization includes centers of expertise that maximize the knowledge of specialists and maintain local offices to maximize proximity to customers and markets. So while a person (say in HR, Marketing, or Finance) may report to a centralized head of their function or region, he or she may also have a solid or dotted line to a business or geography. This dual-reporting relationship is intended to ensure that the specialist doesn’t operate in a vacuum, removed from those whom they support.

Example: "My boss is the VP of Supply Chain for Spain, but I work with the head of the business on a daily basis and also need to make sure that I am doing what the corporate Supply Chain team expects.”

Customer "Hub" Matrix

Companies often have dedicated customer teams whose sole purpose is to work together to meet the needs of specific internal and external customers. More and more, these teams are not fully dedicated to one customer or even customer group. Instead they are a “shared service” that supports a line of products or even an entire business.

Example: “I am the key customer contact for this territory. My company has six different divisions. My customers order products from all six divisions. Most of my job entails negotiating and executing con- tracts across these six divisions. I am all matrix—none of these people report to me.”

What is matrix vs non matrix organization?

What is matrix vs non matrix organization?

If a matrix organization is represented by rows and columns and a more traditional organization works just in columns, here’s how it would be represented graphically:

These non-matrixed organizations operate in columns/verticals versus across the enterprise. Talent, decision-making and strategy are independent of the other columns in the organization.

There are 8 major differences between matrix and non-matrix structure, beyond the basic row/column description:

- Resources are shared across the organization, not dedicated to a singular part of the business

- Increased need for integrated approach for setting goals and establishing priorities, because resources are shared

- Includes some employees with multiple bosses

- Decision-making is decentralized; decisions a made at many different points in the organization, not just at the top

- Decision-making more inclusive

- Increased need to influence others, without authority

- Communication doesn’t follow “chain of command” rather happens in all directions

- Increase work “in the collective” which means much of the work is done in meetings

What does it mean to work in a matrix organization?

What does it mean to work in a matrix organization?

Matrix is the structure; working cross-functionally describes what it takes to navigate it. Several skills and behaviors are critical in working cross-functionally in a matrix organization. To truly find flow and effectiveness in a matrix organization, you start with four building blocks.

Mindset

Adjust your thinking from lanes and intersections to traffic circles and you are halfway there to becoming a matrix master. In The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, Stephen Covey does a great job of explaining how the way you think about something affects your actions and ultimately outcomes. He calls it the See-Do-Get Model. How you approach or see things will determine what you do, which in turn leads to your outcomes. If you want different outcomes, you need to start by changing how you view your situation—your mindset.

Jujitsu

Jujitsu is conceptualized through the “yield” in the traffic circle. Jujitsu is a 2,500-year-old martial art that relies on redirecting the force of your opponent, thereby using his/her energy, not your own. Jujitsu is pertinent to matrix masters because conflict (though generally not hand-to-hand conflict) is what matrix roles are set up to bring out. You can view this conflict as a battle and exhaust yourself fighting, or you can choose to not fight fire with fire. If you don’t compete (for resources, decisions, control, etc.), your opponent can’t win. Instead, try stepping away or disarming the conflict by giving concessions. It may seem counterintuitive and potentially counter to your organization’s culture, but it is a powerful approach that leaves your reputation, values and strength intact.

Zoom Out

Cross-functional work requires more awareness than traditional work, just like traffic circles require different awareness than intersections. Maintaining a narrow, siloed focus on only your small segment of a project or organization will lead to failure. Matrix Masters must be able to see all the pieces of the puzzle at once to figure out whom to involve, communicate with and influence. The traditional perspective of “I focus on this and this only” will only hurt you in a matrix role. Zooming out can be difficult because when we are overwhelmed or confused, our natural human tendency is to pull back and focus on whatever is right in front of us. These blinders may offer temporary relief, but not a sustainable solution. Want to know if you are truly ‘zooming out’ in your thinking and acting?

Triage

Triage is a medical term that refers to the process of efficiently prioritizing patients based on the severity of their condition when resources are insufficient to treat them all immediately. It comes from the French verb trier, meaning to separate, sort, sift or select. Working cross-functionally with a zoom-out mentality, you will see a lot: discussions that need to take place, decisions that need to be made, problems that need to be solved, conflicts that need to be resolved. But seeing them isn’t the same as tackling them. To avoid being completely overwhelmed, you have to triage. I have worked with a number of Emergency Room physicians for whom triage is a way of life. Although the stakes are not quite as high in a matrix role, triage is still vital. You are privy to things you wouldn’t see in more traditional roles. But you can’t take it all on—you have to triage.

In our research, we pinpoint what is most needed to achieve results in matrix organizations.

What’s most important?

- Being trusted throughout the organization

- Knowing your partners’ business realities and processes—not just your own

- Knowing your role in the organization

- Providing information that is easy to understand

- Having partnerships that help you and your team get things done

Where do most people fall short?

- Proactively sharing your priorities and goals with partners

- Focusing on a limited number of goals

- Knowing the priorities and goals of others

- Knowing what information partners need and proactively sharing it

- Anticipating role clarity issues versus getting frustrated when people cross into your “turf”

Which essential is most challenging?

Goal alignment

Which essential represents the biggest potential competitive advantage?

Decision-making

Defining what it takes to work in a cross-functional matrix is absolutely critical. Without a common definition, we are left with a gut feel for what it means to “do it right.” Gut feeling is not enough for team members to have clear expectations of how they will approach the work, let alone for managers to hire and coach for it.

The natural default is for people to focus on, communicate in and act according to their ‘home base’—this narrow thinking (called silo mentality) is the opposite of matrix management. To avoid defaulting into silos, we have to be clear on what it takes and what it looks like to work cross-functionally. Individuals have a sense, and organizations often institutionalize, common definition of what it means to effectively coach, to deliver a presentation, and to give feedback. But there is no common mental model of what it means to work cross-functionally. We fall back on proclamations to “break down silos!” and “act like an owner!” But without a common set behavioral expectations, the pull of the silo is just too strong, no matter how catchy the tagline.

In addition, a lack of common framework leaves leaders flat-footed. Without a common framework, leaders can struggle to find the root cause for a lack of flow; they can resort to generalities for giving feedback to someone who is struggling to gain traction.

The work that Finerty Consulting does focuses on creating common nomenclature and expectations to drive the culture required in a matrix organization.

What are 3 characteristics of a matrix organizational structure?

- Organized around business/product lines and around functions, geographic regions, and/or projects

-

Multiple bosses: Often employees may have more than one boss in a matrix organization. For example, a person might be in the Finance function, supporting Business/Product B and report to a manager in Business/Product B (usually called a direct or solid line reporting relationship) and also have a manager in Finance (usually called an indirect or dotted-line reporting relationship)

-

Complex products/services with complex decisions that are best solved through team members working through resources across the organization to decide and solve problems

These three characteristics are true regardless of the type of matrix structure. The final characteristic serves as a bit of a litmus test. If your organization’s products or services are simple and static from a technology, regulatory or market perspective - you may not need to employ a matrix structure. But when we look at organizations with complex products (complex from a scientific, engineering, technology perspective) spread over multiple locations and markets and potentially subject to significant regulatory and quality guidelines - you get into specialized resources and complex decisions. These two realities lead organizations to consider a matrix organizational structure.

What are the advantages of matrix organization structure?

Advantages of Matrix Organization Structure

- Encourages enterprise-wide thinking and acting, which means stronger strategy alignment and better decisions

- Leverages talent across the organization, versus replicating it, meaning a more fiscally responsible use of resources

- Provides for broader view of customer/end-user needs and ability to flex to these needs by bringing forth the organization's full portfolio of products/services

Disadvantages of Matrix Organization Structure

- Decision-making can be slower because more perspectives, needs, and opinions are considered

- If not properly managed, share resources can struggle to understand and act on priorities across the enterprise

- Higher level of ambiguity (in roles, priorities, decision-making) can be uncomfortable and staggering, leading to increased process and policy in an attempt to eliminate ambiguity and provide clarity

The most significant advantage is truly the breadth of thinking and problem-solving that is possible. A matrix structure done well breaks down our organizational silos. This type of thinking leads to better decisions and innovations that aren’t possible when people are narrowly focused on their part of the organization.

The silo-breaking impact of matrix structures is significant. Nearly every reality of work in the 2020s – digital transformation, fierce global competition, labor shortages, increasingly complex landscape and corresponding decisions – requires organizations to break out of functional, geographic and business unit silos. Businesses see these challenges and know that the solutions are not found in silos, nor overcome in silos. The challenges cut across multiple functions, teams and geographies, as do their solutions. Matrix structure is a way to face this reality through reporting relationships and organization design.

The biggest watch out is how the organization manages the ambiguity. Building a tolerance for ambiguity, increasing communication, and building a culture of trust and partnerships is the preferred course of action. In short, manage the ambiguity through behaviors - don’t try to eliminate the ambiguity through policy and process. Policy and process have a place in every organization, but left unchecked creates an overly bureaucratic, low-engagement culture. This is the natural path for matrix structure that organizations must fight against.

What does a dysfunctional matrix organization look like?

Dysfunction in matrix organizations happens when the matrix structure is present, but behavior is not. If the signpost of an effective matrix organization is “flow”, then you get the opposite of flow when behaviors don’t align with the matrix structure. A few common experiences:

- Lack of trust leading to communication miscues and extra work

- Over reliance on process, policy and other bureaucratic methods to make it “work”

- Frustration with lack of alignment of goals and priorities; people working at cross-purposes

- Power struggles, fighting for power, or the belief that only through power can you get things done

- Decisions that everyone thinks are “theirs” or that no one wants to own

- Delayed and derailed decision-making as teams struggle to land on decisions

- Over inclusion or under inclusion in communication and decision-making

- Over-scheduled calendars

It’s no wonder most people experience these realities and quickly settle back into their ‘silo’ or begin to resist the matrix structure. Functional, location and business silos are fast—there is clarity, common purpose, shared language, a common boss. There is comfort.

Making a Matrix Structure Work

Making a Matrix Structure Work

There are six keys to making a matrix structure work:

- A strong compelling “why” behind the structure that everyone in it knows and believes in; the matrix is seen as not just a structure, but as the organization’s operating model

- A strong link between the structure, strategy and goals and culture. Strategy is supported by (and even reliant on) structure and culture to come to fruition

- An honest acknowledgement of the realities of a matrix—it is more ambiguous; decision making is more inclusive of perspectives so it will take longer; you will need to rely influence versus power and authority to get things done

- A commonly understood and expected set of cross-functional behaviors to ensure the organization realizes the benefits of a matrix structure

- A commitment to manage ambiguity through defining, coaching and rewarding behavior - not through policy and process

- Ongoing discussion of the matrix as an operating model and how to make it better individually and collectively.

Who Is The Real “Boss” In a Matrix Organization?

This is a question that pops up frequently. It illustrates the kind of absolute thinking that kills effectiveness in a matrix. Bosses aren’t real (or fake for that matter). If you have more than one boss, it’s not a matter who is ‘real’ - it’s a matter of who plays the different roles.

Here is a typical set up for two bosses:

Here are a few guidelines for making this solid/dotted more-than-one boss reporting relationship work:

Power Struggles in The Matrix Organizational Structure

“You will have to give up power for partnerships,” is the reality of matrix structures. The resources you need to drive your objectives, execute your strategy may not report to you. You will have to rely not on organizationally sanctioned power and authority, but on your own ability to build trust and partnerships to influence.

This mindset and subsequent approach is perhaps the biggest shift matrix practitioners must make in order to navigate cross-functionally. Matrix structures redistribute power and decision-making, placing it in corners of the organization closest to the technology, issue, customer or market.

Often we build matrix organizations, but the power still remains at the top—the big decisions are still made at the top. When this happens, you have people stuck in a strange hybrid organization where the structure calls for dissemination of power, yet those in senior positions are unwilling or unable to let go and trust the decision-making of others in the organization (often closer to and more expert than they are). This hybrid results in fits and starts—teams that start strong, but lose engagement after a few decisions get vetoed or taken out of the team; lack of trust because the ‘talk’ says empowerment but the walk says authoritative decision-making. If leaders cannot trade power for influence, then the matrix will ultimately lead to a highly disengaged workforce - impacting retention, innovation, customer experience and ultimately the bottom-line.

Conclusion

The three advantages of matrix organizations—encouraging enterprise-wide thinking; leveraging of resources, and the ability to anticipate and react to customer needs across the portfolio—are compelling.

But matrix organizations are susceptible to bureaucracy when organizations enlist the structure without behavior expectations and attempt to achieve flow in the matrix structure by eliminating ambiguity through excessive policy and process.

Defining what it takes to work in a cross-functional matrix is absolutely critical. Without a common definition, we are left with only a vague notion of what “good” looks like. This is not enough for team members to have clear expectations of how they will approach the work, let alone for managers to hire, coach and reward for it.

With a common language and expectations of behaviors, organizations are able to use ambiguity to drive agility, move efficiently even in the collective, and find the advantages of matrix organizations while avoiding unnecessary bureaucracy.

Organization structure is like the frame of a house - but it’s not the house. Just as the house frame doesn’t provide shelter, the matrix organization structure itself doesn’t ensure enterprise-wide thinking and deciding, leverage of resources or encourage agility.

Those outcomes are a result of an intentional focus on cross-functional behavior. When these behaviors are expected and delivered, there is a sense of ease; a sense of flow. Flow means decisions are made and implemented smoothly; tasks and work move through the organization—all fed by an ongoing supply of information. For most organizations, if they achieved this flow, it would be their competitive advantage.

SCHEDULE A CONSULTATION WITH THE FINERTY TEAM